The Presence of a Troubled History

I’d like to invite you on a city tour with a difference—a Belfast city walk in search for interfaces, peace walls, murals and neighbourhoods away from common tourist places. Belfast, the capital of Northern Ireland (or Ulster). For 30 years, the city was the stage for a low-key, yet gruesome, civil war known as The Troubles, which has now been over for nearly as long. I remember seeing images of riots and terror on the evening news when I was young, but I couldn’t make much sense of them. The conflict was presented as a fight between Catholics and Protestants, which was true but very misleading. In reality, it was a struggle over identity between people of Irish descent, who wanted to be part of Ireland, and those of English and Scottish descent, who chose to remain British. It was a fight between Republicans and Unionists, with their religious affiliations simply a reflection of their origins.

I was surprised to find that this history still shapes the city so profoundly today. You’ll see what I mean when you follow our photographic city walks. Rather than visiting popular tourist spots like the Titanic Museum and downtown areas, we’ll explore many of the neighborhoods on the outskirts. We’ll walk along “Peace Walls” and interfaces. We will go to were people actually live.

The project was my son Malte’s idea. He’s a photographer and filmmaker based in Berlin who works with analog film, while I was trying out my new Fuji XT50 on this trip. I’ll include some of his images in this post, marked with an “M.” You’ll probably be able to tell which ones are his, as his style is quite different from mine.

Note: You may click on any image to see it large

A very brief history

On Good Friday 1998, a peace treaty was signed in Dublin, officially ending a 30-year civil war in Northern Ireland (Ulster) known as “The Troubles”. This name, a grim understatement for a conflict that cost the lives of over 3,500 people, has a long history behind it.

To understand the conflict, we must look back centuries. The British had dominated and ruled Ireland for an extended period. In 1607, after a revolt by Irish chieftains, London expropriated their land in what was known as the “Plantation of Ulster.” Private entrepreneurs received the land for cultivation, and settlers from northern England and the Scottish lowlands were recruited to work it. By the end of the 19th century, the descendants of these settlers made up the majority of Ulster’s inhabitants. Unlike the Catholic Irish, they were predominantly Protestants. (See here for more details).

In 1921, Ireland gained independence from Britain, but the province of Ulster chose to remain with the United Kingdom. From that point on, Northern Irish politics became dominated by Protestant Unionists, while Catholic Irish people faced severe discrimination. They often struggled to find jobs, their housing situation was terrible, and they had virtually no say in political matters, even in areas where they were the majority. (For a detailed review see here).

The situation came to a head in 1968 when a newly formed Civil Rights organization held rallies demanding fair rights. The protests quickly turned violent, marking the beginning of a bloody 30-year struggle between Republicans and Unionists—a conflict that would become known as “The Troubles.”

Belfast, an overwiew

This map of Belfast, created by Malte, effectively illustrates the city’s sectarian divides. The east is predominantly Protestant (orange), while the southwest is largely Catholic (blue). In contrast, the south is a more affluent, mixed area (grey) without the sectarian divisions seen elsewhere. The north contains a mix of both Protestant and Catholic neighborhoods, resulting in many “interface” areas where the two communities meet.

Central Belfast is unique because it is considered a neutral zone. The colour on the map really doesn’t matter here. The City Center serves as a hub for shopping and leisure for all residents, where the topic of one’s neighborhood or background is essentially taboo.

The map also shows peace walls and gates. The data for population distribution are from the 2001 census, with the map overlay applied according to the Ward Reform of 1993. Note that this creates a statistical blur. For example, Ballymacarrett (east) is marked “mixed” in its entirety, ignoring the purely Catholic neighbourhood of Short Strand nestled within. On a ward level, however, the numbers are 50:50 Protestant/Catholic – and therefore, mixed.

Duncairn Gardens (the North)

Duncairn Gardens, the street where we stayed, served as an interface between a Republican and a Unionist neighborhood. It is enclosed by two walls that run along both sides, though they aren’t very dominant and were easy to miss at first glance. It’s also a surprisingly beautiful street with many trees, which is rare in Belfast. The walls have nicely designed gates to each of the neighboring communities, which, like all similar gates in the city, are locked at night.

The Belfast City Marathon, first held in May 1982 during the height of the Troubles, holds significant social and anti-sectarian importance. Its route deliberately crosses numerous interfaces and runs through many working-class neighborhoods, which were the most affected by sectarian divisions and the conflict itself. Despite this, the organizers do not emphasize the event’s social relevance. Instead, like the city center, the Marathon is regarded as a neutral and unifying event for the city.

That Sunday morning, my son wanted to go into the adjacent Republican New Lodge area to take some photos. He returned just five minutes later: the gate was closed, even on a Sunday. Even as the runners were making their way down Duncairn Gardens, the gate remained locked. What we couldn’t make sense of was that the opposite gate, which leads to the loyalist neighborhood, remained open.

“The Troubles aren’ over. They aren’t over.” – “But we have peace now” I say. ” – “Yes, we have peace.” She turns away and mumbles: “They aren’t over.”

From a conversation with an elderly neighbour at Duncairn Gardens

Troubles

Two of many incidents that occured at Duncairn Gardens during the Troubles and after:

26–27 June 1972 – Mass shooting at Duncairn Gardens/Edlingham St

Rival crowds clashed; multiple bursts of gunfire were directed into the area. Seven people were shot, and William Galloway (18) died of his wounds. (Hansard)

7 Dec 2001 – Pipe-bomb attack at the Hillman St / Duncairn interface

Two Catholic teenagers escaped injury when a pipe-bomb was thrown over the peaceline near Hillman Street and Duncairn Gardens. (Cain)

Tiger’s Bay (North)

As we walk through the gate from Duncairn Gardens into loyalist Tiger’s Bay, we are welcomed by an angel. There is no sign or inscription to clarifiy the meaning of the statue. The neighbourhood is rather quiet and very tidy.

The lower end of Tiger’s Bay presents a more overtly sectarian impression, expressed by many murals. The image on the far right depicts scenes from World War I, a common theme in loyalist neighborhoods. These murals frequently celebrate the heroic contributions of Ulster soldiers in both World Wars.

New Lodge (North)

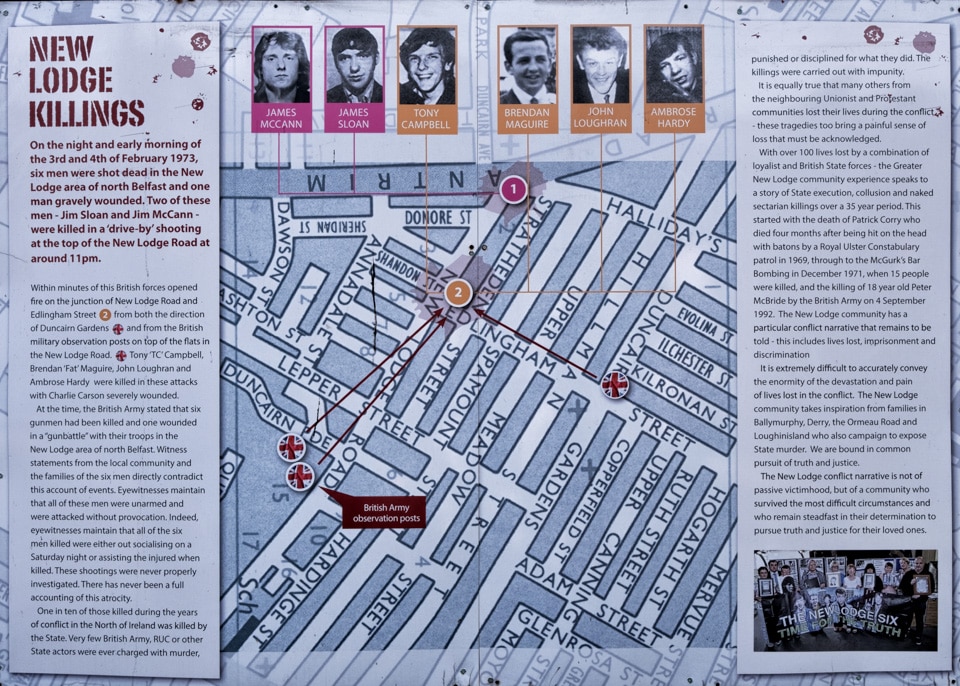

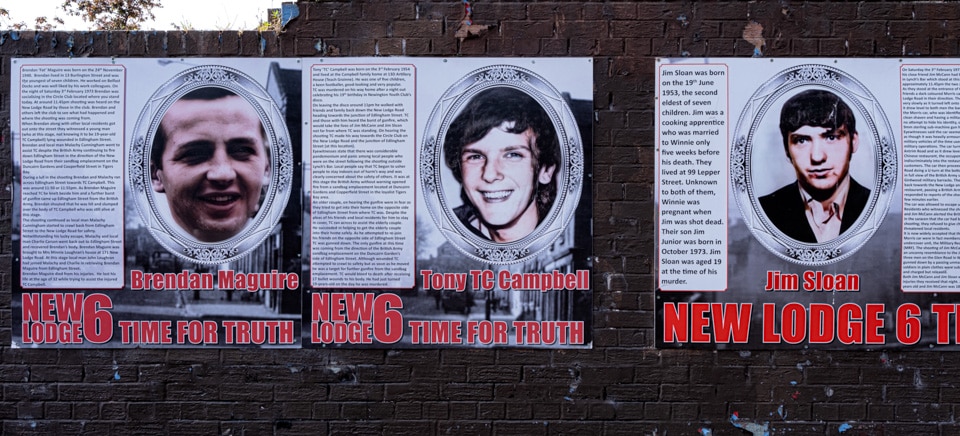

In addition to the well-known Falls and Shankill areas (which we will visit below), New Lodge was also a major hotspot during the Troubles. According to CAIN (Conflict Archive on the Internet), 105 people were killed in this area between 1969 and 2001. That is slightly more than 2% of the local population! As expected, a significant number of murals in the area serve as memorials to these dark times.

Troubles

An article from the BBC in February 2021 reported that the Attorney General had ordered a new investigation into the so-called New Lodge Killings of 1973. The article recalled the events of that day:

On February 3, 1973, two men were shot by a gunman in a car as they stood outside Lynch’s bar. Later that same day, Anthony Campbell was celebrating his 19th birthday when he was hit 17 times as he ran to help an elderly couple get into their house. Two other men were also shot as they tried to drag Campbell out of the line of fire. A sixth man was shot in the head after he came out of the bar waving a white cloth. All of the men were unarmed.

It’s a chilling detail that a high-rise flats building on the lower end of New Lodge Road served as a British Army sniper post. It was equipped with night-vision equipment and it is widely believed that the four men were shot from this building.

A peaceful city

“It’ strange. We are the friendliest people to outsiders, but we always fight among ourselves.”

Quoting a taxi driver from memory

By now you might have the feeling that Belfast is a dangerous and forbidding place to go. The opposite is actually true. The people are friendly and easy going. I was repeatedly given permission to photograph private scenes. However, I did sense a slightly stronger suspicion in Unionist areas. The Protestant population has a more defensive attitude, as many feel they have been falsely blamed by the outside world for centuries of oppressing their Catholic neighbors.

Ardoyne (Northwest)

From the Marrowbone Millennium Park, you can enjoy a wonderful view of Ardoyne, a predominantly Catholic and Republican working-class neighborhood. It is entirely surrounded by Protestant areas. The area was originally founded as a village in 1815 by a wealthy businessman who built 30 homes for the employees of his damask factory.

Now lets look at the houses a little closer.

Did you notice the wall? Well, actually what you see here is the fence perched atop the peace wall. It towers above the rooftops, cutting directly between the homes on Alliance Ave (Republican) and Glenbryn Park (Unionist). Before the Troubles, this area was relatively mixed. As the violence escalated, minority Protestants and Catholics were forced or chose to relocate to their respective majority neighbourhoods. In just that short stretch of Alliance Avenue, almost 20 people were killed during the 30 years of the Troubles.

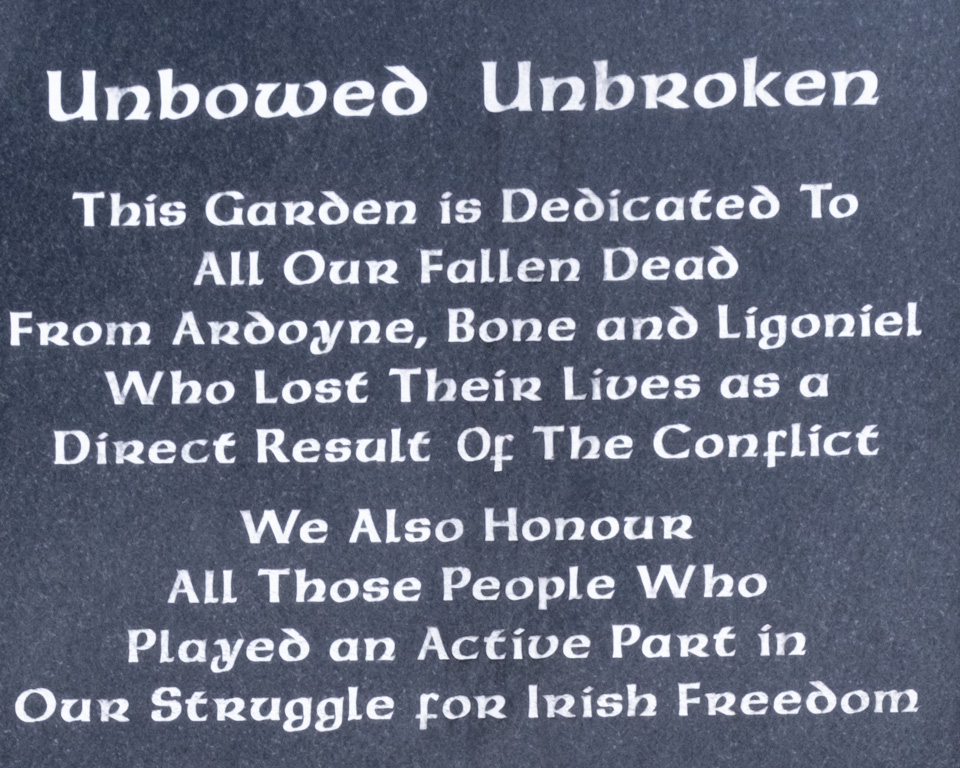

We ask an elderly woman for directions to Holy Cross Church, assuming it is a point of interest in Ardoyne. We have to ask several times; either our pronunciation is unintelligible or her hearing aid isn’t working well. Finally, she opens her gate and gestures for us to follow. Instead of the church, she leads us to a small enclosure between the houses—the local memorial garden. A man is mowing the lawn. Small marble plaques rest on a white stone slab, bearing the names of those who died during the Troubles. There are so many of them.

“Unbowed Unbroken”—remember that phrase. You’ll encounter it again on our tour.

As we continue our walk, photographing things we see along the way, another man approaches us. “Have you seen the Memorial Garden? You must take photos there!”

Holy Cross Church is clearly not what holds foremost importance for the people of Ardoyne.

As expected, numerous murals can be found in Ardoyne. While many depict its grim history, others with more positive messages have appeared more recently.

Despite the Good Friday Agreement, Ardoyne remains one of the places where riots have occurred years later. Below is a brief account of what happened, along with some original footage of the rampage.

The Holy Cross Dispute

The Holy Cross Girls’ Primary School lies adjacent to the Glenbryn estate, across Ardoyne Road. In 2001-2002, three years after the Peace Treaty, loyalist protesters from Glenbryn tried to block the path of young Catholic schoolgirls along that street. I cite from a text of author Colm Heatley:

“Protestants from Glenbryn insisted the schoolgirls would not be able to walk past their estate to get to school because, they claimed, the IRA was gathering intelligence in this way. The Catholic parents were equally adamant that their girls should be allowed to get to school in the quickest way possible, comparing the protesters to the white supremacists of 1950’s Alabama. While an alternative route was available, many Catholic parents refused to use it, asking why should they have to use the back door’, which to them symbolised second-class citizenship.”

“In the 12 months after the protest ended Alliance Avenue was the scene of near nightly rioting between Protestants and Catholics.”

Source: CAIN

Shankill (West)

Upon entering a neighborhood, it’s often immediately clear whether it is predominantly Protestant or Catholic. The Union Jack and other symbols of loyalism replace the Irish flag and those of republicanism; the color orange stands in contrast to green, and the Israeli flag to that of Palestine. Even when it comes to world affairs, Protestants and Catholics seem obliged to take opposing stances.

Rarely, however, was this contrast as stark as when we first entered Shankill Road. The Union Jack and other loayalist flags were everywhere, even stretched across the street.

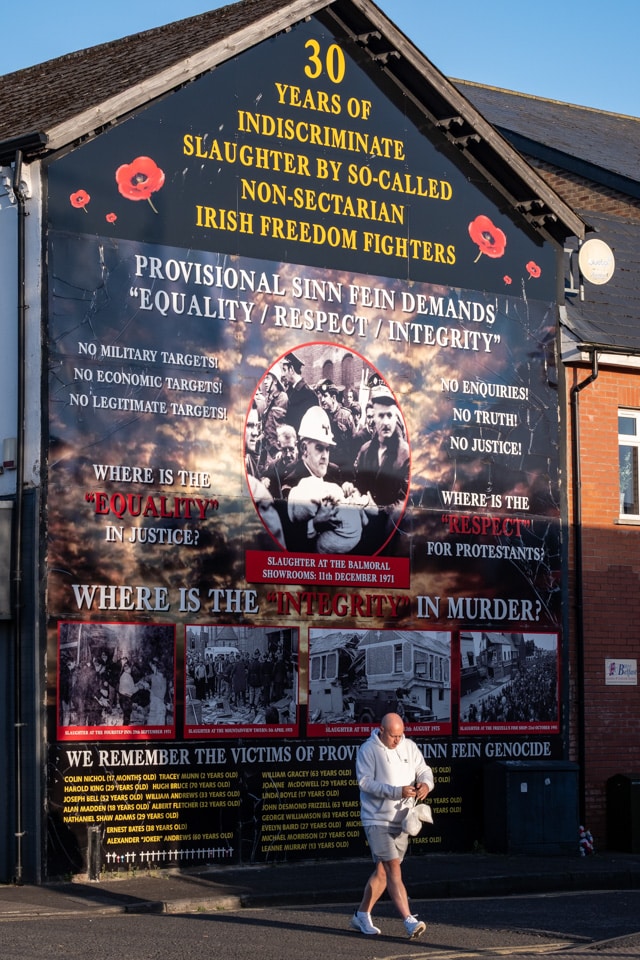

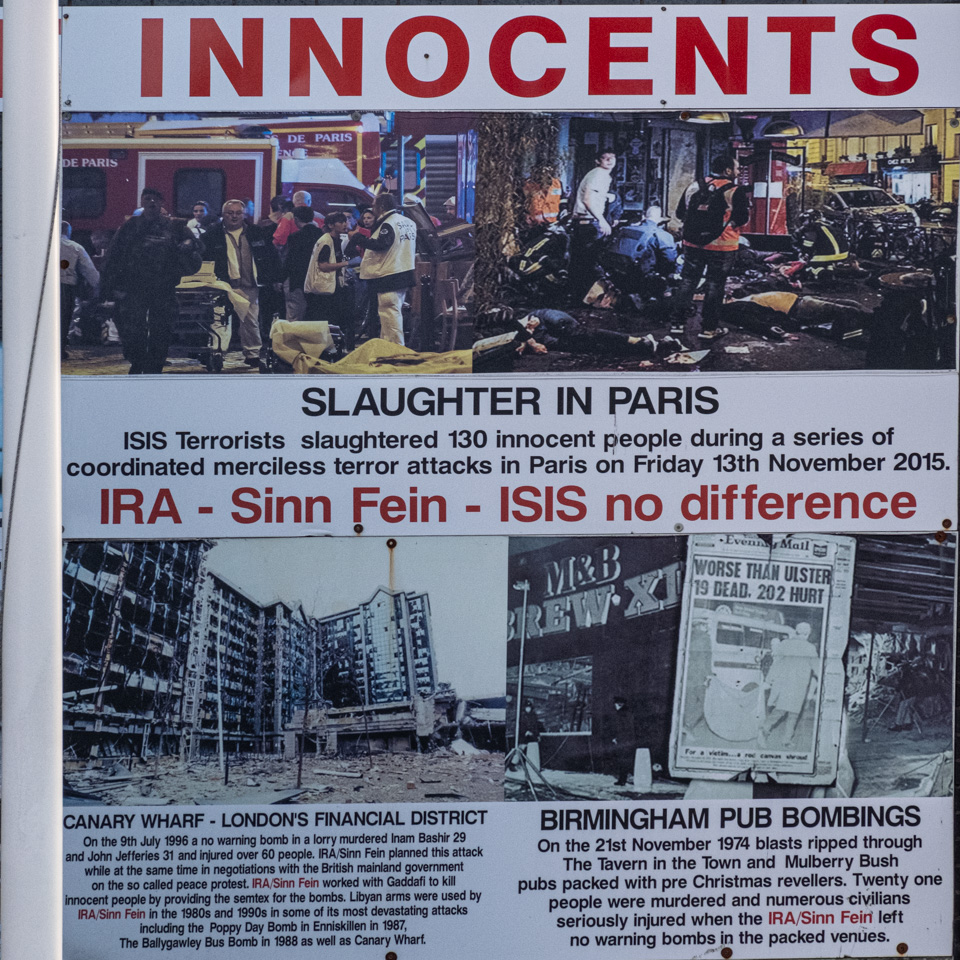

And just a few steps further down we encountered these unmistakable messages.

For an outsider, it’s difficult to understand how people in such conflicts can view history so one-sidedly. After all, the road’s name is forever linked to the infamous Shankill Butchers, a loaylist paramilitary gang active from 1975 to 1982. This group was responsible for the deaths of a least 19 Catholic civilians, none of whom had ties to any paramilitary group. The Butchers’ tactics involved kidnapping, brutal torture and murder. I find it too gruesome to even explain here how they got their nickname.

I think it’s time for some more historical clarifications.

Troubles – the main groups involved

Republican side:

> IRA (Provisional Irish Republican Army) – split 1969 from the Official IRA (which had fought in the Irish war for independence). The IRA understood themselves as part of a world-wide anti-colonialist movement and aimed to force a British withdrawal from Northern Ireland through an armed campain of guerrilla warfare.

> Sinn Féin – political party with close ties to the IRA. Since 2022 the largest republican party in Ulster.

> INLA (Irish National Liberation Army – another split-off from the Official IRA and armed wing of the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP). They aimed for a united and socialistic Ireland.

Loyalist side:

> UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force) – founded in 1966 with the aim to defend loyalist areas and retaliate agains republican attacks. Their political wing was the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP).

> Ulster Defence Association (UDA) – formed later than the UVF in 1971, the UDA became soon the largest paramilitary group on the loyalist side. It was a kind of umbrella organization for various fighting groups. It claimed many attacks under cover names such as Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF).

> Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) – political party founded 1971 by Ian Paisley, a Presbyterian minister and notorious hardlinder. Today the largest political party on the unionist side.

Army and Police:

> The British Army – deployed since 1969. Initially they were welcomed by some Catholics as a peacekeeping force. But this changed soon ofter atrocities of the Army against Catholic protesters.

> RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary – the police force which was recruited almost exclusively from Protestant population. Thus it was viewed as a partisan force by Catholics.

> UDR (The Ulster Defence Regiment) – a locally-recruited infantry regiment of the British Army. Like the RUC, the UDR remained almost entirely Protestant and was a target for republican attacks.

Close to Cupar Way Peace Wall, still on the Shankill side, I have a strange encounter with some kids. As my legs hurt from walking, I sit down besides a young girl, maybe aged 12 or 13. She looks at me: “This is a bad place.” – “Why is it bad?” I ask. – “It’s bad.” – “But why? What is bad?” – “Last week there was a storm.” – Three boys appear, one tries to clarify: “Fighting with them over there.” He points to the peace wall. Me: “But the Troubles are over, it is peace now.” – Him: “Yea, right. Still fight. Have a good day.” All of them disappear.

Phases of the Troubles

The Troubles can be roughly divided into different phases.

> Early Phase (1968-1971)

The conflict began with civil rights protests demanding equal rights for Catholics. 1969, following severe clashes with the RUC and Protestant loyalists, British troups were deployed. The Provisional IRA was formed 1970 and the UDA 1971.

> Escalation (1971-1972)

Internment without trial was introduced as a counter-terrorism measure; however, the vast majority of those detained were Catholic nationalists. A huge protest march in the city of Derry/Londonderry provoked the British Army to open fire, killing 26 unarmed protesters. The event remains remembered as Bloody Sunday. The IRA grew rapidly in number, whilst loyalist groups felt threatened and increasingly resorted to retaliatory attacks, often on Catholic civilians, as the IRA was a difficult target.

> Tit-for-tat violence (Mid-1970s)

Although paramilitary groups on both sides claimed they would attack only “legitimate” targets, in the mid-70s more and more civilians were murdered purely along sectarian lines. Pub bombings became frequent, and many attacks were be brutally retaliated. In this stage, civilian deaths outnumbered those of security forces..

> Ulsterisation and Hunger Strikes (Late 1970s – Early ’80s)

After the Sunningdale Agreement, a first attempt to implement power-sharing in Ulster, was brought down by Unionist resistance, a general strike and notably, Ian Paisley’s agitation, the Government in London persued a new strategy: the Ulsterisation of the conflict. From that point on, the RUC, not the Army, was to be mainly in charge of curbing violence. Internment was ended, and detainees were to be treated as criminal prisoners. They, in turn, demanded to be treated as prisoners of war. This ultimately led to the 1981 prisoner hunger strike, led by Bobby Sands, which saw 10 inmates starve to death. Bobby Sands bacame a martyr, and the IRA saw this as a major succes in gaining fresh public support.

> The Long War (The 1980s)

The IRA revised its structure, operationg mainly from small, clandestine cells. They prepared for what, in their view, would become a long war – a war they also carried beyond Ulster. 1984 they attempted to kill Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at a Conservative Party Conference in Brighton. In Northern Ireland, however, the momentum of the conflict slowed, and the death toll was lower than in the previous period.

> The Peace Process (The 1990s)

By the late 1980s, there were first signs that republicans were looking for an end to the conflict. Fighting continued, but, unknown to the public, there were cautious initial contacts across the conflict lines. These negotiations finally culminated in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

The Peace Wall (Cupar Way) and Falls (West)

The best-known peace wall in Belfast runs for about a kilometer along Cupar Way, separating the Shankill area to the north from the Falls area to the south. Shankill and Falls are often considered the epicenter of the Troubles in Belfast. The wall between the two areas is more than 10 meters high. It has also become a major tourist attraction (perhaps second only to the Titanic Museum).

We first approach the wall at Northumberland Street, where we meet other tourists for the first time. A driver of the “Black Cab Tours” is explaining a Unionist mural to them. These tours are quite popular with visitors, taking them to major historical sites. The topics of this particular mural included the Boer War, the UVF, World War I, World War II, and solidarity with Israel.

We finally reach the beginning of Cupar Way. Surprise! There is a mural just being created. And its message is…

“I want to make something brighter, more positive. Working on roses now, you know, the old ladies will enjoy these. Better to see once I have painted the plaster work.” – “Still troubles around here?” I ask. – “O yeah, some bricks from that side once in a while.” – From which side?” I point north and south. – “Both sides” she answers.

From a conversation with the artist

As we speak, some young bike-riders drive by. Their demeanor seems somewhat aggressive. As we finally start our walk along the peace wall, the riders return. They notice my camera and give me signs. At the time, I assumed that they are showing me the finger. Later, I go through my shots and realize I am wrong.

But what do these gestures stand for? The three-finger sign of the boy in the middle is not easy to form and must be deliberate. So, I ask my AI bot about the gesture, and without hesitation, it tells me this is a UDA sign, the three fingers standing for the three letters of the paramilitary group. Later, while composing this text, I ask it again. Its reply is the same. Then, I ask it for sources. After a while of deliberation, the AI replies that it could not find any. Yet another AI bot insists that the original answer is correct. Such signs “are part of a subculture of visual and non-verbal communication that is understood by those within the community. The lack of verifiable sources for such a gesture is not unusual”. Do I believe the AI? If you happen to know that gesture, please tell me about it in the comments.

It gets quieter as we walk along the wall. Then, I encounter an almost poetic scene and take a picture I really like. You’ve seen it already, but I want to show it again because it’s my favorite.

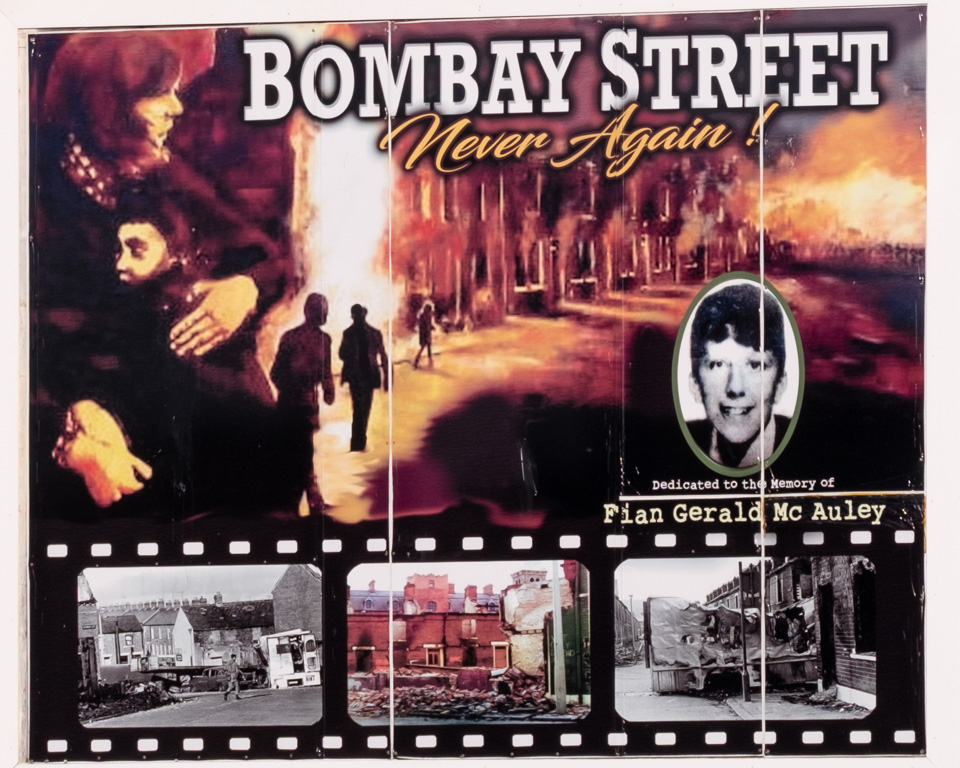

Bombay Street

To reach the Catholic Falls side of the peace wall, we walk to the end of Cupar Way and then circle a large industrial estate. Fenced complexes like this, as well as major highways or railroad tracks, often serve as interfaces, too. Behind it, we run into Bombey Street. It begins with a small memorial garden that tells of a truly gruesome history.

The quote above is from The Irish Times. The report goes on: “On August 14th, republicans had exchanged shots with the RUC and loyalist gunmen along the nearby interface with the mainly Protestant Shankill area.” Shortly before, the British Army had been deployed in Ulster to support the local police force. But the following night, when the loyalist mob burnt down the houses on Bombay Street, the Army refrained from action. The Irish Times cites a contemporaneous chronicler: “The soldiers were useless . . . they retreated and fired a tear gas bomb and there was silence for a while except for the crackle of 60 or so houses burning.”

This incident prompted a radical shift in Catholic opinion. As the Irish Times puts it: “A honeymoon period in which the Catholic nationalist community had viewed the British army as their saviours from loyalist mobs had been replaced by open hostility.” Soon thereafter, the Provisional IRA was formed.

The depth of the trauma still becomes clear as we view the rebuilt houses from the back. Large metal cages run from the roof down to the bottom, securing the buildings from petrol bombs. And this is despite the fact that the peace wall, over ten meters in height, already protects them from their loyalist neighbors on the Shankill side.

Yet, life goes on. People arrange with the situation and enjoy a warm and sunny spring day. Of course, I ask before I take a picture like the one below. On some occasion, I even told kids who asked to be photographed to call their parents for consent. People are always very friendly and mostly consent to me photographing them, except for one instance at Tiger’s Bay, when a group of children on a playground asked me for a picture of them. As soon as the nearby adults noticed this, they approached me in a rather aggressive manner, yelling at me to stop and go away.

The Village (South)

I hope you are not too tired from our rather uncommon city walk. There are two more quarters left that I want to introduce to you: The Village and Short Strand. To tell the truth, I myself was very tired from walking when we visited those neighbourhoods. We stayed one week in Belfast and explored every part of the city that I describe here on foot. Belfast is not a big city and walking to your destinations is mostly feasible. Taking the bus, however, is often rather cumbersome. The lines are arranged in star-shaped pattern, all leading to the city center. They avoid crossing through community interfaces. Thus, in order to reach the next neighbourhood, it is often more convenient to just walk (or, of course, take a taxi).

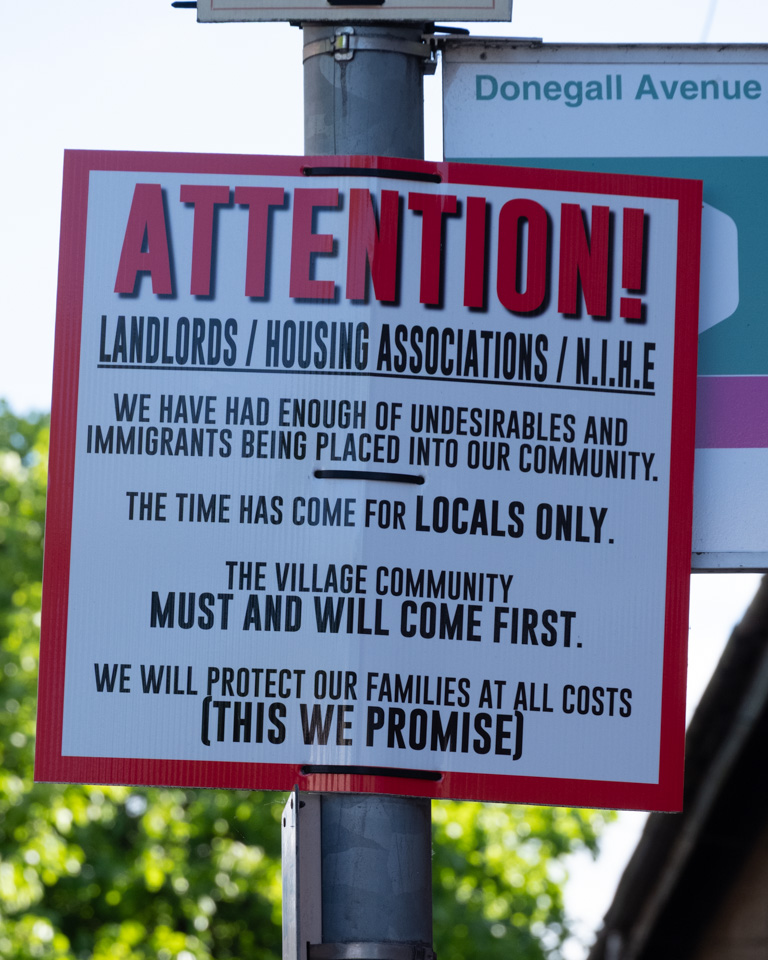

“The Village” is an informal name given by locals to their neighborhood, which is situated around Donegall Road. Historically, it was a predominantly Protestant neighborhood with low-quality housing and a stronghold of the loyalist paramilitary forces UDA and UVF. It lies squeezed in between the railway line coming from Grand Central—which separates it from the more affluent and less sectarian areas of South Belfast to the east—and the M1 motorway, which serves as a “natural” barrier toward the Catholic Falls area to the west. Murals and other signs leave no doubt that this is a place of staunch loyalism.

However, the topics have changed with time. Nowadays, support for Israel and anti-migration themes are highly en vogue in loyalist quarters. The latter often appear under the slogan “Local houses for local people.” I find the tone in the poster which I show you below quite aggressive. And I wonder how this must feel to the residents with a migration background, of whom we saw quite a few in the streets. This is still a poor neighborhood, and they probably can’t afford other places easily.

From the Tates Avenue bridge, we get a view down into Donegall Avenue. While Donegall Road was a notorious hotspot that saw numerous sectarian killings during the Troubles, Donegall Avenue (running at right angles to it) is a quiet residential street. No incidents are reported to have happened here during the conflict.

Short Strand and Cluan Place (East)

The Short Strand neighbourhood is so small that, at first, we don’t even find it from the bus stop (yes, we took a bus this time). It is a tiny Catholic spot nestled within the Protestant east of Belfast.

Every turn we take ends in front of a high wall. We try again, walking around the southern tip of what our map shows as Short Strand. We turn right once more and enter a dead end: a short street between two rows of houses with an almost eerie atmosphere. We have come across Cluan Place.

Do you remember the phrase “unbowed, unbroken”? We have seen this before at the Republican memorial of Ardoyne. Obviously both sides use the exact same slogan for their diametrically opposed views!

As Short Strand is a walled enclave in the loyalist east, Cluan Place is a walled enclave within republican Short Strand. As you might guess, this meant a precarious situation for both neighborhoods during the Troubles, and the tensions did not end with the Good Friday Peace Agreement.

Troubles

St Matthews is a Catholic church at the northeastern interface of Short Strand. The area was the scene of a notorious gun battle in 1970 when three Protestants were killed. The IRA claims they were defending St Matthew’s Church from mob assault; loyalists retort that three people were shot dead as they returned from a parade.

In June 2002 – four years after the peace agreement – another bloody conflict was sparked at St. Matthews. As loyalists celebrated a royal jubilee, residents of Short Strand accused them of draping Unionist red-white-blue buntings on the rails of the church. This raised tensions which culminated in hand-to-hand fighting between up to 1,000 republicans and loyalists. At least three people were injured by gunshots. Police accused both the IRA and UVF of having orchestrated the fights.

Cluan Place was affected badly from these clashes. A resident described what he had seen: “”On Monday, a gunman climbed up on to the roof of a house behind us and shot two people putting up boarding over the windows.” What came next infuriated the residents even more: “I saw him dancing. He was pleased with what he had done. We could hear cheering from his supporters on the other side of the wall.”

Source: The Guardian and Wikipedia

Source: The Guardian

Hit the North (City Center)

“Hit the North” is the title of an ’80s punk track from The Fall. The song became quite popular in Northern Ireland and something of an anthem for Northern Pride. Accidentially or not, it is also the name of Belfast’s annual mural and street art festival.

The Fall: Hit the North

So, we do walk down to the city center after all, specifically to Kent Street and Union Street in Belfast’s Cathedral Quarter. This is the locacion of the block party, where local and international artists come together to bring a lot of colour into the city.

Like our whole week, it is an exceptionally warm and sunny day, and the atmosphere at the festival is relaxed and peaceful. With the exception of some references to LGBTQ, all the art we see is apolitical. And there are certainly no hints of the Troubles. “Hit the North” is a festival of the next generation, a manifestation of the joy of life and an optimistic outlook for the future.

This would have been a nice conclusion for this already lengthy blog, wouldn’t it? But, sorry, there is still a little more to say. And again, it has to do with politics. In 2016, 55.8% of Northern Ireland said No to the “Leave Europe” referendum. But Brexit came anyway, and Northern Ireland was drawn into a dilemma. After Brexit, there had to be a hard customs border between Britain and Europe, and thus between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This, however, was expressly prohibited by the Good Friday Agreement. A temporary solution was found by shifting the customs border to the Irish Sea, i.e., between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, while there are still no controls between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. You might guess that this enraged the loyalist community and reinforced their long-standing feeling of being abandoned.

In fact, when the Brexit transition period ended at the beginning of 2021, rioting and clashes began in various areas, including Belfast. Protesters—primarily Unionists—attacked police with petrol bombs, bricks, fireworks, and incendiary devices, resulting in dozens of injured officers. This was seen as a manifestation of the building anger and alienation among Unionists over the Irish Sea border arrangements for Northern Ireland, which came into effect the same year.

Source: The New Statesman

Tensions remain high, as is stated in a recent report of the US Congressional Research Service. Yet, our personal feeling from walking the streets of Belfast is more optimistic. The young people we talked to showed a keen interest in an economically and socially brighter future, one not tainted by the sectarian past. Here is a short excerpt of a conversation we had with a young man in the city center. As you know by now, we could not ask about his community, but you might guess from his answer. The topic was the referendum, proposed in the Good Friday Agreement, of staying with Britain or uniting with Ireland.

“Some time ago I would have tended to stay with Britain. But now… you know, Ireland is doing much better economically then Britain after the Brexit.”

And now I finally conclude this blog with an example of typical Irish humour: the signboard on the outside of the Sunflower Bar in Kent Street. Thanks for following thus far!

Listen to young people speaking for themselves about what it is like to grow up in Belfast

Notes

Date of journey: May 2025

Usefull sources of information:

My latest Posts

- Belfast Unseen – a Photographers’ City Walk

- Toraja – the culture behind life and death

- Story of Nutmeg and the Banda Islands

- Jakarta's Old Town (Kota Tua)

- Slums of Jakarta

Leave a reply

This was a really interesting read. Coming from Belfast, I am used to people being curious about my city. it was refreshing to find that Collin has really worked to understand the city on a deeper level. Thank you for visiting Belfast and showing her many sides. I hope you allowed yourself a pint of Guinness in the Sunflower Pub. It’s a good wee place to rest.

Thank you Helen. Being from Belfast your words mean a lot to us. And no, too many people wanted that pint in the Sunflower that day, but we had the Seafood Chowder in the Cafe Ceoil! Besides all other, Belfast is also a very entertaining city.

entertaining and very informative!